On any cardiac ward, the steady beep of monitors tracks hearts fighting for time. Some patients wait for a donor organ; others rely on pumps that help keep blood moving when muscle fails. These devices, ventricular assist systems and extracorporeal pumps, can be a crucial support in moments of crisis and offer possibilities when standard treatments may not be enough. Their parts are engineered, but their trajectories begin in classrooms, animal labs, and regulatory hearings. The path from idea to bedside is lengthy, expensive, and public. It requires not only invention but also persistence and documented evidence.

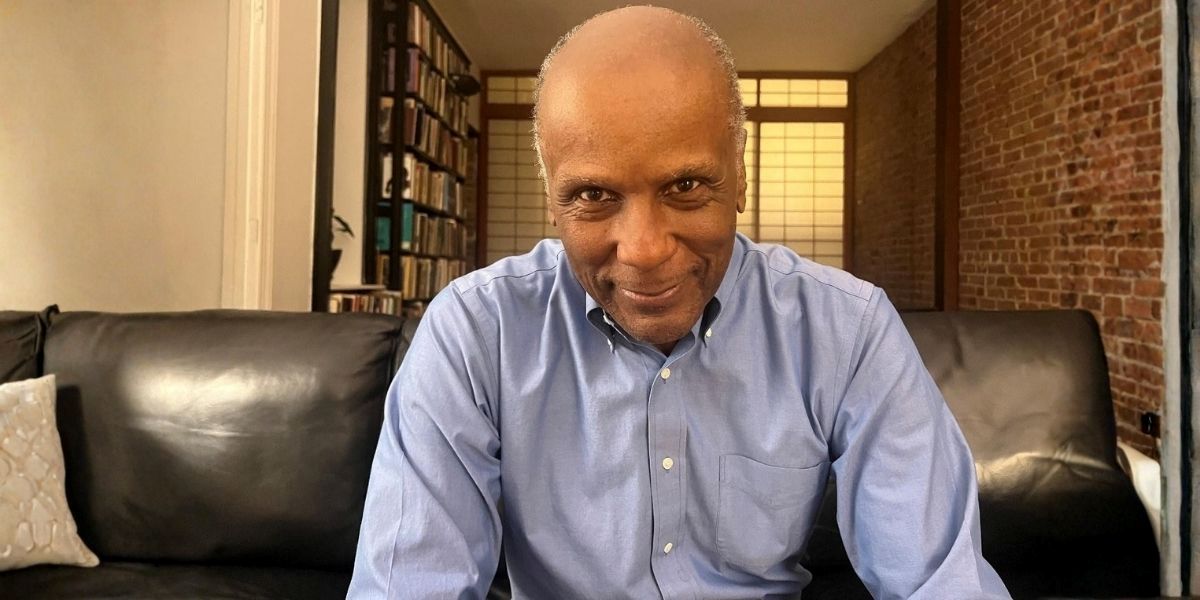

Kurt A. Dasse, Ph.D., has built a career at that intersection. A physiologist by training and a medical-device executive by vocation, he has worked across academic benches, preclinical programs, clinical trials, and boardrooms that help determine whether a technology can reach patients. This article traces Dasse’s work from early muscle physiology through the HeartMate era to magnetically levitated pumps and nitric oxide therapy platforms. The scope runs from early experiences with left-ventricular assist devices to the standards that later programs continue to follow.

Dasse was born on July 7, 1949, in Valparaiso, Indiana. Early exposure to science was an important influence through coursework and lab work that guided him toward physiology rather than clinical practice. He earned a B.S. in biology from the University of Massachusetts Boston and a Ph.D. in physiology from Boston University.

His doctoral and early postdoctoral work centered on muscle physiology and blood–surface interaction, areas that would later prove to be relevant when he entered the world of blood pumps. He learned and taught methods that have become essential for translational programs: transmission electron microscopy for ultrastructure, histology for tissue changes, and hemodynamic monitoring to capture how interventions may alter pressure, flow, and resistance. The lab’s questions were basic: how tissue adapts under hypoxia; how alcohol affects muscle mechanics, but the tools and habits were carried forward.

At the Boston University School of Medicine, Dasse helped design medical physiology courses and directed a surgical dog lab in which students could observe real-time cardiorespiratory responses. He then moved into joint roles with Tufts University’s Schools of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine, where two lines of work would later become important for the future: a percutaneous access device (PAD) for long-term implants and a transcutaneous energy transmission system (TETS) to power implanted pumps.

Those programs sat alongside early LVAD exposure at Boston centers. Dasse participated in animal implants and early clinical observation, while documenting preclinical results for National Institutes of Health contracts. The routine of quarterly and annual reporting, methods, outcomes, adverse events, and necropsy findings laid the foundation for the discipline that later supported regulatory submissions. The bridge between classroom and animal lab was becoming a career path: turn physiology into design constraints; turn design into test plans; turn test plans into data that regulators and surgeons can trust.

In 1985, Dasse shifted from pure academia to applied research at Thermedics, working on catheters, grafts, and dialysis access. The learning curve was commercial as much as scientific: materials selection for manufacturability, sterilization effects, and clinical workflow.

He then co-founded Thermo Cardiosystems (TCI). The company’s central program, HeartMate, pursued an implantable LVAD at a time when long-term support was still uncertain. The 1980s constraints were clear: driveline infections, thrombus formation, pump reliability, and patient selection. Dasse’s remit spanned clinical trial design, data integrity, and the FDA’s pre-market approval (PMA) pathway. HeartMate’s progression, from implantable pneumatic to vented electric to subsequent generations, was a process that required iteration under scrutiny: texture and hemocompatibility refinements, infection-control practices, and adverse-event tracking that could stand in front of panels.

HeartMate I and later HeartMate II are recognized as his most widely acknowledged contributions within TCI and, after corporate transitions, within Thoratec’s portfolio. The devices did not eliminate heart failure; they provided specific patients a path to transplant or destination therapy with known risk profiles. In parallel, Dasse remained engaged in early work on nitric oxide use around LVAD implantation, foreshadowing a later focus.

From 1997 to 2000, Dasse served as Chief Scientist and Vice President within Thermo Electron’s biomedical group. The role broadened his lens beyond circulatory support to respiratory ventilators, neurodiagnostics, imaging, and anticoagulation instruments. Portfolio oversight introduced structured risk analysis, post-market surveillance management, and M&A diligence. The lesson was cross-disciplinary: each device family has its own failure modes and regulatory cadence, but quality systems, design controls, and clinical-engineering partnerships remain important common currency.

After Thermo Cardiosystems, Dasse co-founded Levitronix’s U.S. medical business and later served as president and CEO. The company developed magnetically levitated centrifugal pumps for short-term and pediatric support: CentriMag for adults in cardiogenic shock or during surgery, and PediMag/PediVAS for children. The MagLev approach addressed bearings and wear, chronic issues in earlier generations, by suspending the rotor in a magnetic field to reduce friction and blood trauma.

Work with a Swiss engineering team overlapped with technology that would later underpin HeartMate 3’s motor platform. While corporate transactions moved assets between companies, the technical continuity remained visible: flow-path optimization, controller logic, alarms, and the manufacturing tolerances that keep pumps within spec during long hospital runs.

Dasse later led GeNO LLC, which pursued inhaled nitric-oxide delivery systems for pulmonary hypertension and cardiopulmonary support. The combination-product model, device plus drug, requires coordination between FDA centers responsible for devices and drugs, with attention to gas purity, monitoring, and safety interlocks. The program intersected with his earlier LVAD experience: right-heart strain after LVAD placement is a known concern; targeted pulmonary vasodilation can assist in the perioperative period and beyond.

He also took roles at VADovations, which worked on a miniature percutaneous pump approach for heart-failure phenotypes, including HFpEF, and later co-founded consulting and development entities focused on extracorporeal MagLev systems and regulatory strategy.

Assessing impact in mechanical circulatory support is not simply about a single patient and more about norms that persist. Across the HeartMate family, CentriMag/PediMag lines, and related platforms, several standards have emerged: prioritize hemocompatibility by minimizing shear and stasis; reduce infection risk at percutaneous interfaces; design controllers for clear alarms and data capture; and maintain surveillance that feeds design iteration. Those norms are visible in later devices from multiple manufacturers.

Patient reach may be difficult to quantify precisely in an article like this, but the categories are clear: bridge-to-transplant and destination-therapy LVADs for adults; short-term support for surgery and shock; pediatric pumps for low-weight patients who lack implantable options; and gas-delivery systems for defined cardiopulmonary indications. Dasse’s roles, which include executive leadership, trial design, and advisory posts, sit within those channels.

Parallel to his scientific output, more than one hundred journal articles and book chapters, Dasse writes fiction that draws on medical, legal, and ethical settings. Titles such as Law and the Heart, The Sleep Doctors, and Gifts of Life use various characters to explore responsibility, consent, and the cost of progress. The novels do not serve as evidence for his device work; they translate career themes into narrative form: how institutions handle risk, how evidence moves a case forward, and where personal motives collide with public duty.

Beyond company posts, Dasse has served in professional societies and on advisory boards: as president of the American Society for Artificial Internal Organs (ASAIO), participating in pediatric LVAD oversight (including NIH PumpKIN activities), and serving in advisory roles with start-ups working on blood pumps and related technologies. These positions reinforce the iterative nature of the field: centers generate observations; companies adjust designs; societies convene and critique.

Four decades in assistive circulation and cardiopulmonary devices tell a consistent story about translation. Academic labs refine hypotheses and methods. Preclinical groups turn those methods into standards. Clinical teams manage complications and document outcomes in accordance with protocol. Executives raise capital and accept public accountability when recalls or adverse events occur. Dasse’s career sits across those layers. Later profiles will examine specific episodes, trial milestones, pediatric feasibility efforts, and the combination-product pathways that are shaping how gas therapies and pumps enter practice. Here, the record shows a steady movement from physiology to devices that, for certain patients, provide a critical bridge that biology may not have been able to offer.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this article is for informational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice. The medical devices discussed, including ventricular assist devices (VADs) and related technologies, are designed to assist patients with heart failure. However, individual results may vary, and the effectiveness of these devices depends on various factors, including patient condition and treatment. Please consult a qualified healthcare provider for personalized medical advice.